Share post now

Article

Switzerland must withdraw from the Energy Charter

05.12.2022, Trade and investments

The Energy Charter Treaty protects companies that invest in fossil fuels. A growing number of countries are withdrawing from it, while Switzerland continues to thwart the energy transition.

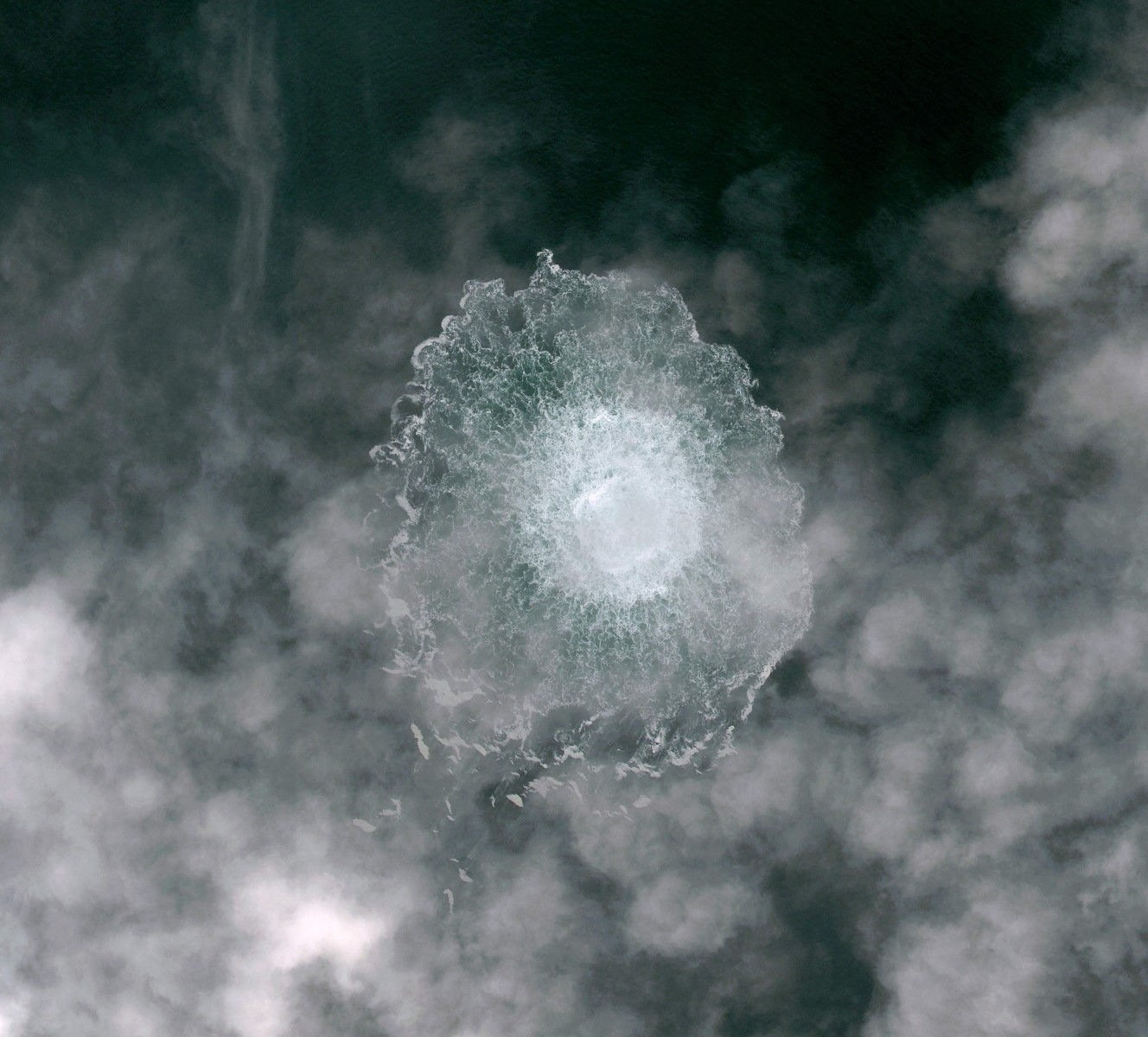

The Nord Stream gas pipeline leak in the Baltic Sea, photographed by the Pleiades Neo satellites.

© AFP Photo / Airbus DS 2022 / Keystone

The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) has been in force since 1998 and forms the basis on which companies can sue a State if they believe that their investments have made a loss owing to some government intervention. Most of the 53 signatory States are industrialized countries like Switzerland and the EU Member States, but countries like Afghanistan, Yemen, Mongolia and some in Central Asia are also on board.

In 2019, for example, Nord Stream 2 AG filed a suit against the EU decision relating to an EU Gas Directive amendment under which intra-EU pipelines would be subject to the same rules that govern those coming from outside the EU. According to the company, these provisions conflicted, among other things, with the principles of fair and equitable treatment, most-favoured nation treatment and indirect appropriation, all of which are envisaged in the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT).

Let us recall that Nord Stream 2 was meant to transport natural gas from Russia to Germany, but the operating company – a Swiss company – went bankrupt early this year. It did in fact belong to the Russian state-owned company Gazprom, but was headquartered in Zug. The controversial pipeline never began operations, as Germany blocked the project on 22 February 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Six complaints by Swiss investors

Of the 43 known requests for arbitration filed by Swiss investors, six are based on the Energy Charter Treaty: three were brought against Spain. Of these, two are still pending, while the decision went in favour of the investor OperaFund in the other. OperaFund had accused Madrid of introducing reforms affecting the renewables sector, including a 7 per cent tax on power generators’ revenues and a reduction in subsidies for renewable energy producers. Alpiq lost a case against Romania, while another against Poland was decided against Swiss investor Festorino.

According to Transnational Institute calculations compensation claims by foreign investors are at least EUR 7 million. It is no surprise therefore that Germany, Spain, France, Poland and the Netherlands have decided to denounce the Treaty. Oher European countries are currently pondering withdrawal. "I am observing with concern the return of hydrocarbons and the fossil fuels most damaging to the environment," French President Emmanuel Macron is quoted as saying in the "Le Monde" newspaper "The war on European soil should not make us forget our climate obligations and our commitment to reducing CO2 emissions. Withdrawing from this treaty is part of the strategy."

According to the latest figures published by the Energy Charter Secretariat, 142 complaints have been filed on the basis of this Treaty; the number could be far greater, however, as States are not required to notify them. The Treaty therefore breaks all records in terms of complaints filed. Germany, for example, has been sued twice over its decision to give up atomic power: in the case "Vattenfall v. Germany (I)", the amount of the compensation paid by Berlin to the Swedish company is not known; in the case of " Vattenfall v. Germany (II)", the Swedish company received USD 1.721 billion in compensation.

Switzerland unwilling to withdraw

Switzerland, for its part, has so far never been sued on the basis of the ECT. Only a single investment arbitration case has been brought against the country – by an investor from the Seychelles – albeit not based on the ECT. It is still pending. Is Switzerland considering denouncing the treaty? "No", replies John Christophe Füeg, Head of International Energy Affairs in the Swiss Federal Office of Energy, and adds: "The Treaty's critics are overlooking the fact that it applies only to foreign investments. In other words, domestic investments or those from non-signatory states are not covered by it."

In his view, the latest version of this Charter, adopted by Switzerland, should drastically reduce the number of cases and limit the scope of the Treaty. “The EU will now count as a single party, which means that complaints by investors within the EU are now out of the question”, he adds. Consequently, the ECT becomes a treaty with effect in the EU, the United Kingdom, Japan, Turkey, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Switzerland; the remaining parties have virtually no investors. But the fact is that more than 95 per cent of fossil fuel investments in the EU are either internal EU investments, or made by non-contracting parties. This, for example, enables some EU Member States to merrily continue promoting hydrocarbons (e.g., Cyprus, Romania, Greece and the Netherlands). “The argument to the effect that withdrawal is crucial to climate protection is not acceptable, as less than 5 per cent of investments in fossil fuels is impacted. The remaining 95 per cent is beyond the scope of the Treaty."

According to Füeg, a survey was also conducted amongst Swiss investors with assets in the EU. The respondents indicated that they value the legal protection they enjoy under the ECT. "Switzerland would harm its own interests by withdrawing", he concludes.

Adapting the Treaty is not enough

But even the modernised version of the Charter, which is insufficient to combat climate change, is not about to enter into force. Although it was due to be approved by the States Parties at a meeting on 22 November in Ulan Bator, Mongolia, the modernisation was taken off the agenda after EU Member States failed to agree.

For Alliance Sud, Switzerland should join the other European countries that have already taken the step and leave this treaty, which allows a foreign investor to sue a host state for any regulatory change – closure of a coal-fired power plant, exit from nuclear power, change of regulation in renewable energies, etc. – and thus hinders the energy transition and the fight against climate change. It is not acceptable for foreign investors in fossil fuels to be above national laws and to have recourse to a private justice system that too often awards them millions or even billions in damages.