Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

17.03.2022, 2030 Agenda

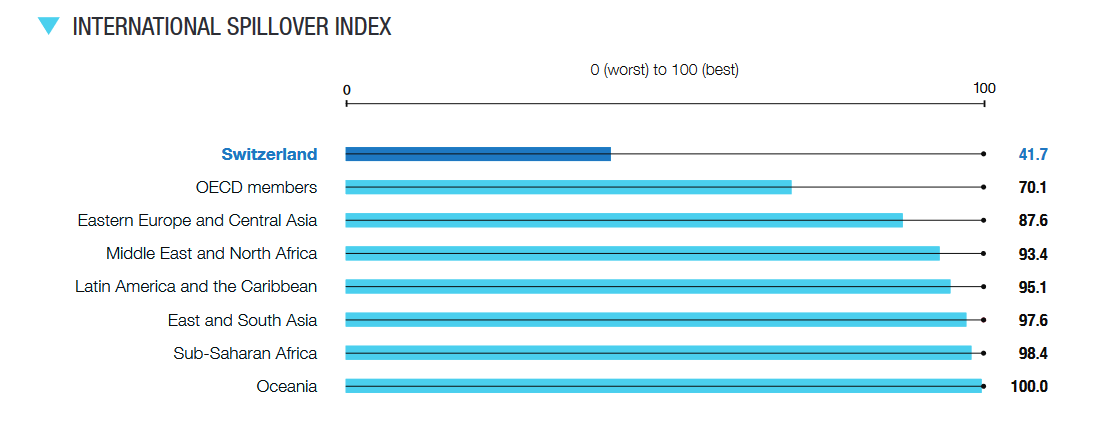

Switzerland's many negative spillovers include environmental pollution, arms exports and tax evasion – and they are undermining international efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

International Spillover Index

© Sustainable Development Report 2021

The globalised exchange of goods, capital and information has increased exponentially in recent years. This exchange also means that supposedly local decisions can have global implications. The year-round consumption of tomatoes, cucumbers and aubergines in Switzerland, for example, directly impacts Europe's vegetable gardens in southern Spain, where massive amounts of groundwater and pesticides are used to produce food under dubious conditions. Such effects are called 'spillovers'. The term is applied when specific actions in one country produce adverse effects in other countries and further hamper their progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

The UN 2030 Agenda, which encompasses 17 Sustainable Development Goals, attempts to take account of these spillover effects. In today's interdependent and interconnected world, all UN Member States in 2015 committed to implementing the 2030 Agenda. How can individual countries implement the Agenda in a globalised world? There is no way around spillovers in that process.

In the Sustainable Development Report (SDR) published annually by authors associated with US economist Jeffrey D. Sachs, all 193 UN Member States are ranked according to their spillover performance. Spillovers are classified into the three dimensions of 'Environmental & social impacts embodied into trade', 'Economy & finance', and 'Security'. In the latest 2021 ranking, Switzerland occupies an inglorious 161st place. The only countries more poorly rated for their spillover effects are the United Arab Emirates, Luxembourg, Guyana and Singapore. In the European ranking, Switzerland comes 30th among 31 countries. How could Switzerland, the model pupil, possibly do so badly?

Trade-related spillovers encompass international effects bound up with the use of natural resources, environmental pollution, and the social impacts stemming from goods and services consumption. Switzerland does very badly when it comes to imports of virtual water, nitrogen, nitrogen dioxide and carbon dioxide, and endangering the biodiversity of ecosystems. These partly invisible by-products arise all along the value chain, in connection with the production and use of pesticides and fertilisers, irrigation, and the use of combustion engines for production and transport, among many other things. Anyone who is reluctant to believe the international figures may also refer to MONET 2030, the Federal Statistical Office's national indicator system. There too, nothing foreshadows any reduction of the substantial material footprint or the greenhouse gas footprint.

Small, resource-poor countries are obviously dependent on goods and services from abroad. This makes it all the more important for these trading relations to be sustainable. The Federal Council's response to an interpellation by National Councillor Roland Fischer (Green Liberal Group, glp) on reducing Switzerland's spillover effects is as modest as its reduction of its footprint. Switzerland is advocating for the UN to set ambitious goals for sustainable consumption and production patterns. The country is also championing the circular economy, and relevant measures are to be drawn up by the end of 2022. It remains to be seen whether they will bring about any significant reduction of Switzerland's material and greenhouse gas footprint.

International efforts to establish sustainable value chains are much more promising. The recently adopted UN Human Rights Council Resolution is expected to formalise the basic right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment (see also here). France's loi relative au devoir de vigilance and Germany's Lieferkettengesetz show both countries to be pursuing similar aims. By comparison, it is becoming clear that the counterproposal to the Responsible Business Initiative will not "achieve" much more than glossy brochures of no consequence, put out by the marketing departments of major corporations.

As regards ‘Economy and finance’, Switzerland's performance is poor to very poor for all four indicators. The problems are obvious. At 0.48 per cent of gross national income (GNI), official development assistance is still below the 0.7 per cent enshrined in the 2030 Agenda. The Swiss financial centre remains a safe haven for tax dodgers. Automatic exchange of information on financial accounts is taking place on a limited basis only. And finally, multinational corporations in Switzerland are still able to optimise taxes at the expense of the poorest. In the absence of specific measures to combat tax avoidance and profit-shifting by companies to low-tax jurisdictions, Switzerland is failing to fulfil its responsibility toward poorer countries.

The third area, that of ‘security’, encompasses the potential negative and destabilising repercussions of arms exports on poor countries. In this area too, Switzerland performs rather poorly owing to its weapons exports. Since the SDR was published, however, there has been an initial step in the right direction, in that the counterproposal to the Corrective Initiative (Korrektur-Initiative) ensures that no war materiel is exported to countries engaged in civil war or where there are systematic and grave human rights abuses. The export regime is being enshrined in law, thereby placing the necessary democratic control over war materiel exports in the hands of the people and the Parliament.

The Sustainable Development Report attracts repeated criticism for insufficient and incomplete data and the choice of indicators. Yet this should not distract from the global responsibility incumbent on Switzerland's lawmakers, domestic economy, and people. All stakeholders must ensure that Switzerland's policy decisions contribute to global sustainable development and not to water pollution, poverty or population displacements. In the final analysis, not only do spillovers from rich OECD countries adversely impact other countries, they also hamper international efforts to achieve the 2030 Agenda.

Laura Ebneter, JPO at Alliance Sud

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.