Share post now

Investigation

Switzerland in the dense fog of carbon offsetting

20.11.2024, Climate justice

With the purchase of new cookstoves, Ghana is expected to save more than 3 million tonnes of carbon emissions, thanks mainly to women – as a substitute for emission mitigation in Switzerland. Alliance Sud criticises the project's glaring lack of transparency and highlights controversial details that project owners attempted to hide from public view.

A girl cooks with her mother in her home in Tinguri, Ghana.

© Keystone / Robert Harding / Ben Langdon Photography

Grace Adongo, a farmer from Ghana's Ashanti region, is happy with her new and more efficient cookstove. Instead of cooking on an open fire, she now places the pot on a small stove. She needs appreciably less charcoal, which both saves money and mitigates carbon emissions. This testimonial comes from the latest Annual Report of the Ghana Carbon Market Office and coincides with many others that are reporting on the numerous cookstove projects throughout the global carbon market. These projects supposedly help provide poorer population groups with cookstoves that are more efficient and less harmful to health than traditional stoves or fireplaces, which generate large amounts of smoke. This reduces wood consumption and carbon dioxide emissions (how much is highly controversial – but more on that later).

The principle involved is always similar. The cookstoves are sold cheaply. This entails customers transferring to project owners their rights to the emission mitigation outcomes. The emissions saved by the new stoves are then calculated over the ensuing years and sold internationally by the project owner as carbon certificates. The proceeds from the certificates are needed to subsidise the cookstoves.

From the personal standpoint of people like Mrs. Adongo, what sounds like a good thing is also precisely that. But the system as a whole is much more multilayered and contradictory. The case mentioned at the start, the Transformative Cookstove Activity in Rural Ghana, which Alliance Sud examines in detail in this paper, revolves around the government carbon offset market in which Switzerland imputes the emission mitigation outcomes achieved in Ghana to its own climate goals. A surprising number of venues also come to light in the process, and also warrant critical assessment from the standpoint of climate justice. Switzerland's cooperation with Ghana is also a good example of why the trade in certificates under the Paris Agreement is not conducive to attaining the ambitious climate goals.

Carbon certificates from this and many other projects are being paid for with a 5-centime tax assessed on each litre of fuel at Swiss petrol pumps. Owned by motor fuel importers, the Foundation for Climate Protection and Carbon Offset KliK provides the money for mitigation projects in Switzerland and abroad. Through carbon offsetting abroad, Swiss lawmakers aim to compensate for climate mitigation actions not taken in Switzerland, so that they are still able to meet the climate goals of the Paris Agreement.

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, Switzerland undertook to halve, by 2030, its greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990. With the CO2 Act, however, only about 30% of emissions can be mitigated in Switzerland – barely more than before the law was revised in the spring of 2024. The remaining 20% must be offset abroad. Under the Federal Council's savings package announced in September 2024, climate mitigation activities in Switzerland are also expected to diminish. The inevitable consequence is that Switzerland will need more carbon offset certificates if it is still to achieve the climate goals. That is not the meaning of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, under which the transfer of emission mitigation outcomes to other countries should lead expressly to "higher ambitions". To achieve this, Switzerland will have to ensure that the climate goals of both countries are consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Switzerland has promised net zero by 2050. Because net zero is to be achieved globally by that same year, Switzerland therefore expects other countries also to set their net zero target at 2050. Measured against this yardstick, there are substantial gaps in Ghana's national contribution, up to 2030, towards the realisation of the Paris Agreement. Ghana has announced only a non-binding net zero target for 2060 and excludes oil production from its climate goals. When contacted in that regard, the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) writes: "The requirements of the Paris Agreement apply", and points towards the unilaterally set climate goals based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities. "In the process, climate goals must encompass the highest possible ambition and subsequent goals must be even more ambitious." However, there are no other criteria for the climate goals of a partner country.

A year ago, Ghana announced the expansion of oil production, adducing the lack of financial support for climate protection as the reason. This illustrates the fundamental problem: the countries in the Global South lack the international climate finance that should be forthcoming from the Global North by way of support. The upshot is that they opt for what they see as their second-best solution for raising funds, that of selling the outcomes of their climate mitigation activities as carbon certificates. The difference with climate finance is that Switzerland obtains the "right" to postpone its climate mitigation measures. On balance, ambitions for effective climate mitigation are being lowered, not raised.

Dense fog in February

Ghana and Switzerland approved this cookstove project in February 2024 under the bilateral market mechanism of the Paris Agreement (Art. 6.2). It is being implemented by the Amsterdam-based company ACT Commodities (project owner, see Box 2) and is projected to record a 3-million tonne reduction in carbon emissions by 2030. It is therefore incumbent on both governments to ensure that the project fulfils and maintains high quality requirements, which it promises to do. The Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) verifies the relevant project documentation and publishes them upon authorization.

The project owner is ACT Commodities, an international conglomerate headquartered in Amsterdam. On its website, the company describes itself as the leading global provider of market-based sustainability solutions that is driving the transition to a sustainable world. ACT is a major player in emissions trading. But the company prefers to avoid too much transparency – its own website fails to mention that the conglomerate also has oil and fuel trading in its portfolio (through its sister company ACT Fuels, which has no website). This comes to light thanks only to a perusal of the Dutch commercial register. Since July 2023, ACT Commodities has also owned a company that supplies marine fuels, the dirtiest of all fuels. The conglomerate is therefore one of a growing group of commodity traders doing business with fossil fuels and simultaneously "greenwashing" themselves as players on the carbon market.

But the very first look at the documents reveals a lack of transparency: the project is as opaque as dense fog. Extensive passages in the project description are redacted, including virtually the entire analysis that is meant to prove that the project will lead to additional emission mitigation (see chart). But many other relevant facts and figures were also concealed. And the document containing the calculations showing why the CO2 reduction should amount to 3.2 million tonnes was not even published in the first place. That is not what transparency looks like.

Alliance Sud requested publication of the unredacted documents and calculations pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FoIA) – and had to wait four months owing to the project owner's initial refusal. Much, though not all of the project documentation was released thereafter. The passages that were still redacted were supposedly business secrets. It is now also becoming clear that in the original document, many places had simply been arbitrarily concealed.

Excerpt from the analysis of the project's additionality, originally redacted altogether.

Emission mitigation is being overestimated by up to 79%

The calculation methodology whereby the project in Ghana is expected to save 400,000 tons of carbon emissions annually over eight years is a key piece of information regarding carbon offset projects. Reputable certifiers in the voluntary carbon market require project owners to disclose these calculations. These data must be made available for scientific analysis – especially since a growing number of studies are identifying cases of over-crediting of emission mitigation through carbon certificates, including for cookstove projects.

In this case, however, the project owner is reluctant to do so – an unacceptable lack of transparency. Alliance Sud submitted an FoIA request and obtained a PDF copy of the calculation tables. Without being able to view the integrated Excel formulas, verifiability remains limited.

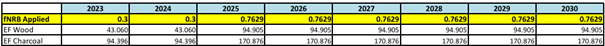

But the figures now available offer surprising revelations. The PDF document containing the calculations shows that for the years 2025-30, emission reductions for the same stoves are being calculated at almost twice as much as for the years 2023-24. The underlying reason is obviously a planned increase of the most key metric, namely, the fraction of non-renewable biomass (fNRB). This is an estimate of the amount of wood biomass by which the harvesting of fuelwood exceeds its natural rate of regeneration. Only reduced use of non-renewable fuelwood can be regarded as a reduction in carbon emissions. The metric is multiplied directly by the other factors and is therefore crucial to calculating emission mitigation. The overstating of the fraction of non-renewable biomass (fNRB) is the main reason for the sometimes-scathing criticism elicited by cookstove projects launched to date for emission mitigation purposes.

For anyone keen on the details, the project documentation showed an fNRB set at 0.3, which is more conservative than for many previous cookstove projects. According to the official UNFCCC reference study dated June 2024, this is an appropriate standard value, as it avoids massively overstating emission mitigation and is also consistent with the country-specific value contained in the study for Ghana, which is 0.33. However, the project now has a clause enabling Ghana and Switzerland bilaterally to adjust the fNRB retrospectively (upwards). The fact that concrete calculations are already being done, from 2025 onwards, on the basis of an fNRB of 0.7629 only comes to light from the PDF document containing the calculations, which was not originally published. The project description fails to mention that plans are already being laid using a higher value, even though it is still to be validated. The value 0.7629 comes from the outdated "CDM tool 30" which is deemed by the FOEN itself to be insufficient as a basis. In the spring of 2024, Ghana invited tenders for an independent study to determine a country-specific fNRB value for Ghana – obviously in the hope that a markedly higher value can be validated. If Switzerland is also to accept it, the study must pass the peer review by UNFCCC bodies. In the light of the aforementioned widely accepted reference study which calculates a country value of 0.33 for Ghana, that is likely to be an uphill task.

A look at the calculation document shows that as of 2025, calculations are to be based on an fNRB – the most important metric – more than two times higher (line in yellow). According to Alliance Sud calculations, this means that between 2025 and 2030, emission mitigation will be overestimated by up to 92%. All told, the overestimation is up to 79% (using the correct calculation for 2023 and 2024).

If a baseline fNRB value more than twice as high is applied, with no basis whatsoever, emission mitigation is being overestimated from the outset. According to Alliance Sud calculations, the project would reduce carbon emissions by 1.8 million tonnes at the most, if the fNRB value is held constant at the more realistic level of 0.3. But the project promises a reduction of 3.2 million tonnes of carbon emissions. It thus overestimates overall mitigation by up to 79%.

Some research lifts the fog…

The absurdity of attempting to describe half of the project documentation as "business secrets" (in the first version of February) is clear from the fact that much of the concealed information is publicly available in other places. If few more minor items of information that had originally been concealed are even available elsewhere in the same document. Further information can be gleaned from Ghanaian Government documents, or can be deduced from other sources.

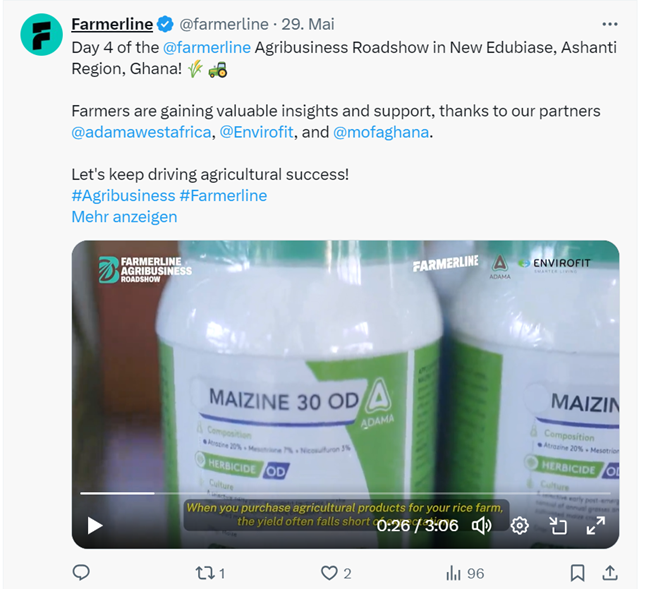

For example, from an online article by the Ghanaian authorities about a visit by the KliK Board of Directors, we learn who is the project's main distributing partner in Ghana – a Ghanaian company called "Farmerline". Farmerline facilitates access for farmers to agricultural inputs, thereby opening up the global agricultural industry to many new clients from Ghana. The project owner also attempted to conceal this connection. Several references to partnerships in the agriculture sector had originally been hidden in the project documentation, and specific cooperation is still redacted. There are reasons, as a closer look will show.

...lingering pesticide spray

In June 2023, Farmerline announced its cooperation with Envirofit, the cookstove producer and the project owner's implementing partner. The project documentation also describes plans to sell 180,000 stoves to rural dwellers within a short space of time, and notes that the stoves will be available at more than 400 businesses for agricultural inputs. But some posts by Farmerline on the "X" platform do arrest the attention of readers. This year, Farmerline conducted an "Agribusiness roadshow" across various regions of Ghana in cooperation with Envirofit – and with the crop protection company Adama, a member of the Syngenta Group. On each day of the roadshow, farmers were presented with the efficient Envirofit cookstoves and Adama pesticides, both being put up for sale. Adama products are identifiable in the Farmerline videos, including three insecticides and one herbicide containing active substances banned in Switzerland and the EU because of their toxicity to the environment and human health. They are atrazine, diazinon, and bifenthrin. Atrazine pollutes groundwater, hampers photosynthesis in plants and is virtually impossible to remove from the environment; it is also classified as a carcinogen. Diazinon attacks not only the pests being targeted but all insects and can also be highly toxic to humans if it comes into contact with the skin. Bifenthrin poses a danger mainly to aquatic animals but should also not be inhaled by humans (see the Pesticide database maintained by Pesticide Action Network).

Sample photo from a Farmerline roadshow video in which the herbicide Maizine 30 OD containing the active substance atrazine – banned in Europe – is also being sold alongside cookstoves.

Furthermore, none of the videos contains a demonstration or the sale of appropriate protective clothing. According to various studies (Demi und Sicchia 2021; Boateng et al 2022; and others), the growing use of pesticides in Ghanaian agriculture is leading to considerable health problems for farmers. In the absence of instructions from dealers, many either do not know how to use the pesticides properly and protect themselves in the process, or they lack sufficient funds to be able to afford protective clothing. Besides, they obtain expert information mostly from their personal circles or from some dealers, but no independent agricultural advice is available. In their study, Imoro et al. 2019 found that 50% used no protective clothing at all and another 40% were not sufficiently protected. Asked whether protective clothing was also being sold at the roadshows, KliK replied that the highest standards of sustainability were of course a prerequisite for their cooperation partners. KliK writes that the issues raised by Alliance Sud with this question lie outside the scope of its discretion.

Thus, attempting to obtain a clear statement regarding the benefits of this offset project for sustainable development is still akin to stumbling around in the dark. Cookstove customers will indeed save money and, as there is less smoke, also hopefully improve their health. Yet, they are simultaneously being urged to spend the money saved on pesticides, the increased use of which is damaging the environment and also creating new health problems in many instances. From this perspective, KliK's assessment of its cooperation partners' "highest standards of sustainability" is erroneous. It is indeed reasonable to strive for synergies with existing players in the agriculture sector in order to reach rural dwellers. But had sustainability been the uppermost concern, a partnership with organisations that promote agroecological approaches would much more likely have suggested itself.

Eye-watering profits for investors

While the new cookstoves enable customers to make financial savings, the project is financially worthwhile for the investors on a much larger scale. It lacks transparency also from a financial standpoint in that the pricing of the stoves is redacted, and the prices of the certificates are a private matter for KliK and its business partners. Moreover, the FOEN is not reviewing a financial plan or anything similar for the project. Yet, from the additional information released following the FoIA request, it is clear that investors are likely to rake in handsome profits. The investors behind this project are invisible, but according to project documentation, can expect an annual return of 19.75% on their investment. A comparison is being drawn with Ghanaian government bonds in order to justify this absurd return. That comparison holds no water whatsoever, as the one thing has nothing to do with the other. The risks associated with investing in a government bond issued by an already highly indebted country are of an entirely different nature – which accounts for the high yields (although it does not legitimise them, as the high interest rates for poor countries are horrific and catastrophic – but again, that is another story).

What this case involves, in contrast, is a project partly financed and secured with quasi-public funds; this could be classified as blended finance, a mix of public and private financing. This is so because fuel importers collect a levy on fuel, by virtue of the CO2 Act. At a purely technical level, should the proceeds of this levy pass through government coffers – as other levies generally do – before being disbursed for carbon offset projects, that would make them taxpayers' money.

That would give rise to a public interest in ensuring that the proceeds from this levy are used efficiently. The funds must go towards climate mitigation and sustainable development in the country concerned, not towards gold-plated returns for investors.

Conclusion

Efficient cookstoves are an inexpensive way of improving the lives of many people while mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, there are considerable contradictions lurking in the market mechanism under the Paris Agreement when implementing climate mitigation projects in the Global South. It is meant to promote sustainable development locally, but is conceived as potentially lucrative business for investors. And while some emissions are being reduced in the Global South, the mechanism offers a political pretext for postponing climate mitigation activities in a country as rich as Switzerland.

Transparency in the certificate trade is therefore the key to discovering the multilayered and potentially problematic background to carbon offset projects. Switzerland's carbon mitigation project in Ghana is a telling example of this. Neither the overestimation of emission mitigation, the sale of toxic pesticides nor the exorbitant yields could be gleaned from the documents that were published following the authorization of the cookstove project. It was only through an FoIA request and further investigation that Alliance Sud was able to clear the fog of non-transparency shrouding the project documentation: what came to light was the approval of reckless calculation methods, business practices by implementing partners inimical to the environment and to people, and a questionable interpretation of transparency by the main players. However, the possibility of public scrutiny remains crucial to ensuring that carbon mitigation projects do not endanger implementation of the Paris Agreement.

This case is the second carbon offset project by Switzerland under the Paris Agreement to be looked into by Alliance Sud. A year ago, Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion elucidated the reasons why new E-buses in Bangkok are no substitute for climate mitigation activities in Switzerland.