Share post now

Article

The energy transition and its minerals

21.06.2022,

The invasion of Ukraine by Russian troops has thrown energy markets and geopolitics into chaos and forced many countries to rethink their energy supply arrangements. Over time, the race for “green minerals” will create new dependencies.

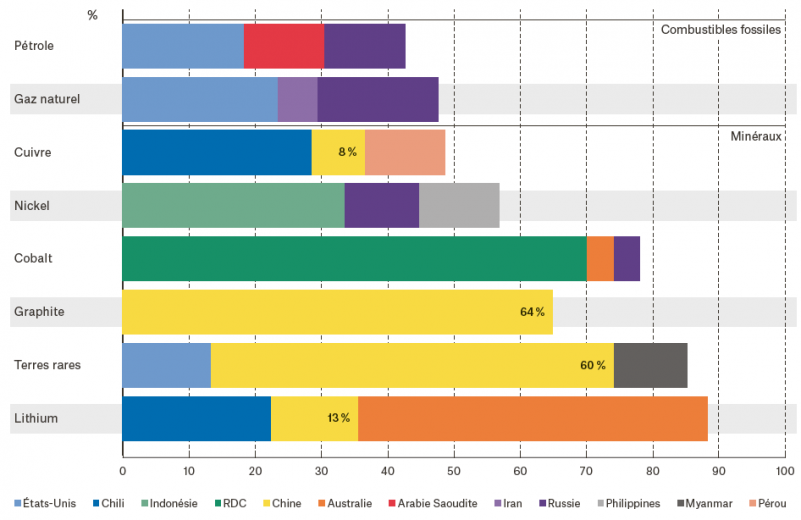

Share of the three largest producing countries in the extraction of selected minerals and fossil fuels, 2019 (Source: IEA) © Alliance Sud / global

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Russia is the world’s biggest exporter of oil, and its natural gas supplies the European economy. The USA, EU and other countries have imposed economic sanctions on Russia and announced their intention to cease using fossil fuels from that country; the G7 Heads of State and of Government have committed to banning or phasing out imports of Russian oil.

The war has prompted political decision-makers to reconsider their energy plans and, in many respects, this could have far-reaching implications, for example, in terms of the looming food crisis, or worldwide endeavours to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The energy crisis

The key question that the world’s leading politicians are now pondering is how to end their energy dependence on Russia. The USA and the United Kingdom have been the first two major countries to ban Russian oil, though their dependence on these imports is only negligible. The EU imported about 45% of its natural gas, more than a quarter of its oil and about half of its coal from Russia in 2021. However, this is likely to change. Following the embargo on Russian coal imposed in April, the European Council decided on 30 May to stop 90% of Russian oil imports by the end of 2022 - with a transition period for Hungary - and the EU aims to reduce its Russian gas imports by two-thirds this year and by 100% from 2027. At the end of March, US President Joe Biden promised to supply Europe with more liquefied natural gas. Europe’s policymakers also held talks with Japan and South Korea about redistributing liquefied natural gas that would otherwise have been intended for these two countries.

On the one hand, the spectrum of options for safeguarding EU energy security in the short-term could include greater use of coal-fired power plants, especially in Germany; on the other, they should be helping to speed up efforts to transition to cleaner energy, especially through increased investment in energy efficiency.

Longer term outlook

The next few years may well be difficult, but they could have positive long-term impacts on energy policy and greenhouse gas emissions in Europe. The electricity sector is subject to the European trading system, which caps cumulative carbon emissions so that a temporary spike in electricity production, from coal for example, would drive up the price of CO2 credits and lead to emission reductions elsewhere.

At the global level, the energy situation is less clear. The war in Ukraine could slow down the energy transition in other parts of the world and drive up greenhouse gas emissions. There could be a significant return to the use of coal, especially in south-east Asia, if Europe effectively corners the international liquefied natural gas market for itself. Then, there is still Russia itself, which accounted for almost 5 per cent of worldwide emissions in 2020 and, in view of its current priorities, will probably make no progress in decarbonization. China, for its part, has announced its intention to increase coal consumption in 2022 to support economic recovery, despite its undertaking to reduce CO2 emissions.

From petrostates to electrostates

Beyond this, the net-zero target set for 2050 will lead to a shift in power from oil- and gas-producing countries to countries that have ample endowments of the commodities needed, for example, to build power networks, batteries and solar panels. The IEA estimates that by 2050, 70 per cent of electricity production could come from renewable sources, which is a massive increase over the current 9 per cent.

The principal elements required for this transformation are a series of minerals including copper, cobalt, lithium, manganese and several rare earths. The IEA has predicted a massive spike in demand for these “green minerals” between 2020 and 2040.

The energy transition holds out the prospect of colossal profits for countries with substantial metal deposits. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the prices of these metals are expected to hit unprecedented and historic highs over a protracted period; the prices of cobalt, lithium and nickel could rise by several hundred per cent compared with 2020 figures. This is undoubtedly bad news for the energy transition. Commodity shortages and the rise of commodity prices could very adversely impact growth, more specifically the sale of electric vehicles. For countries that possess these metal reserves, in contrast, this development would be a blessing, in that it would alter the international financial flows generated from natural resources.

New dependencies and… well-known drawbacks

The production of many of the minerals that are critical to the energy transition is geographically more concentrated than that of petroleum or natural gas. To simplify somewhat, the countries with “green minerals” fall into three categories: Western democracies (such as Australia, which accounts for 52 per cent of lithium production); authoritarian regimes (the Democratic Republic of the Congo produces 69 per cent of cobalt, China 64 per cent of graphite and 60 per cent of rare earths, Russia, 11 per cent of nickel); and democratic emerging countries (like Indonesia, which has 33 per cent of all nickel deposits, Chile, which produces 28 per cent of copper and 22 per cent of lithium, or Peru, which extracts 12 per cent of the world’s copper). Overall estimates are that 50 per cent of “green minerals” are under the control of autocratic or authoritarian regimes. When it comes to further processing, the degree of concentration is even higher, with China being strongly represented in all areas.

This throws up the key question of whether the governments of these mineral-rich countries will harness the growing global demand for and rising prices of these commodities for their own benefit and promote inclusive development by fairly distributing the income generated among their citizens, through appropriate forms of governance. Or whether history will repeat itself, with these countries falling victim to the resource curse. To manage the exploding demand for metals, the IMF suggests that a new international institution be created, similar to the IEA for energy, which could play a key role in the dissemination and analysis of data, industry standards and international cooperation.

Besides, many of the companies that extract these metals face constant accusations of human rights violations and environmental degradation. According to the Transition Minerals Tracker of the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, which oversees the human rights policy and practice of the companies that mine six commodities relevant to the energy transition (cobalt, copper, lithium, manganese, nickel and zinc), almost 500 cases of suspected human rights abuses were observed between 2010 and 2021, with 61 in the year 2021 alone.

(Some) reason for hope

According to some experts, the good news is that by 2050, roughly 40 to 75 per cent of the EU’s needs could possibly be met through recycling, if the major “green metal”–consuming countries make timely investments in infrastructure and scale up their mandatory recycling quotas.

The energy transition and the resulting new geopolitics may therefore be marked by volatility and turbulence, and bring major challenges both for countries that are rich in “green minerals” and for those that depend on them.